How to build on Europe’s strengths

The region regulated by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been the most proactive globally in the early adoption of biosimilars. By February 2023, it had approved around 75 products containing them. The distribution of such compounds within Europe, however, has been uneven, with some countries offering more market opportunities than others. Beyond Europe, few producers have a strategy for the Middle East and/or Africa, and India and South Korea could soon jump in to fill the gap.

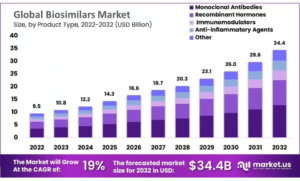

The European Union core (EU5) and the Nordic countries in particular have seen very high market penetration of biosimilars – medicines that mimic specific blockbuster biologics. In general, biosimilars tend to follow the global distribution path taken by their originator biologics, with a key difference: in the area, the European healthcare market is ahead of the US. The popularity of a biosimilars business model has grown steadily and constantly. In 2021, for example, the global biologics market was estimated to be worth almost US$366bn, with biosimilars making up only around 4% of the total (US$16bn). However, according to a report by IQVIA, they saw particularly strong growth of about 80% CAGR in the period 2015-2019. That translates into a near doubling in value annually.

Europe has a lot of them …

The general trend towards high market penetration for biosimilars is expected to continue, as several blockbuster reference biologics are soon going off patent. Two of the latest prominent additions to the list are Avastin/bevacizumab and Lucentis/ranibizumab. It’s interesting to note though that across the major world regions, biosimilar penetration varies widely, and appears to run somewhat counter to conventional economic rules.

One surprising example of this is that the US appears to be lagging behind Europe in the use of biosimilars. Since 2007, only 30 biosimilars have launched in the United States, although at least 10 more are in the approval process and are expected to hit the market by the end of 2023. In addition to the 12 specific active ingredients already being copied (some active ingredients have several biosimilar substitutes), a total of 20 different molecules are then expected to be either approved or in advanced stages of clinical development in the US. In terms of numbers of active ingredients with biosimilar imitation products, the US and Europe are therefore comparable. But the variety of products issued by different manufacturers is much greater in Europe.

The experience has shown, however, that market penetration of biosimilars in the US can happen rapidly. An American study of Community Oncology Alliance practices found a dramatic increase in biosimilar uptake for trastuzumab (Herceptin) – which first hit the market in July 2019 – and bevacizumab (Avastin). In the fourth quarter of that year, participating practices reported 8,000 bevacizumab biosimilar administrations compared to 21,000 for the reference product. In other words, around 28% of all administrations were for biosimilar bevacizumab. By the fourth quarter of 2020, just 15 months later, bevacizumab biosimilars had already reached a share of nearly 60% of all administrations. In addition, participating practices reported a 27% increase in the number of patients treated after the biosimilars entered the market, almost certainly because the therapy had grown more affordable.

Estimates from the Association for Accessible Medicines, the trade association for generic and biosimilar manufacturers, say that savings from biosimilars in the United States will total US$85-US$133bn by 2025. And as Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act kicks in, the landscape should grow even more dynamic in the future.

… but not everywhere

But even when the EMA gives central approval for biosimilars, Europe is not a uniform market. This is because the agency says nothing about availability, nor how a newly approved biosimilar will rank in comparison to the original preparation in the 27 different reimbursement systems of the bloc’s respective healthcare systems.

The latest (2021) biosimilar report from the European industry association Medicines for Europe examines the availability of the 15 biosimilar active ingredients across Europe at that time. All the biosimilars listed were only available without gaps in Germany, France, Hungary and Italy. In Switzerland one biosimilar active ingredient was missing, in Austria two, similar to Belgium and other countries. In the UK, only 10 of the 15 biosimilars were available at the time of the study, which corresponds to a 30% gap in overall supply possible through a marketing authorisation. In some Eastern European countries (with the exception of Hungary), the biosimilar supply gaps were even more pronounced. One reason for this could be the issue of logistics and prioritisation by pharmaceutical manufacturers. But another is reimbursement and models for how reimbursement processes are designed. Free pricing is only used as a model for biosimilars in five European countries.

So … how much will this cost?

All the other countries use regulated pricing’ based on different reference prices and reference pricing systems. One can’t really speak of a uniform EU area, especially when it comes to reimbursement, cost and thus the actual business model. How much cheaper a biosimilar is than the original can vary greatly in Europe. While the Scandinavian countries regularly demand discounts of over 40% for certain biosimilars, savings in France or Italy might only be in the low single-digit range. Market penetration can also generally be viewed as very rapid and significant in Europe, but there are country-specific features there as well. For example, after introduction, the trastuzumab biosimilar in Switzerland was able to gain a market share of just 13% from the previous reference preparation between Q1/2020 and Q4/ 2021 (Source: Biosimilars.ch).

The high approval figures in Europe reveal on the one hand that the EU – and in particular the EMA – created a practicable framework at an early stage to make the process of comparing reference products with biosimilar candidates transparent and watertight. A basic prerequisite is precise knowledge of the reference product in combination with powerful analytical tools that largely predict clinical comparability, subject to confirmation by a comparative pharmacokinetic study.

On the other hand, it is astonishing how differently market penetration happens in individual European nations after a marketing authorisation. In fact, it doesn’t make much sense that equally good but cheaper products don’t spread much more dynamically in financially weaker EU countries, where they would have the greatest impact.

Follow the money …

One possible reason why could be marketing strategy among biosimilar developers. Put simply, this strategy is generally to wrest as much market share as possible as quickly as possible from a blockbuster in its blockbuster market. Various delaying tactics – such as patent extensions, patent infringement suits, formulation adjustments and strong lobbying with the medical profession – can often give the original manufacturer more time to profit from the highest prices. Biosimilar developers are heavily involved in all these defensive battles, but also have to keep an eye on copycat competition and exactly time their own approvals so as not to compete with the original too early or too late.

But even if all this works out in a biosimilar developer’s favour, it still has to negotiate prices amidst competition for reimbursement by respective healthcare systems. In Germany, for example, there is currently a lot of criticism of what’s called automatic substitution’. This rule dictates that a patient’s health insurance company determines via price negotiation which biosimilar is to be administered in place of an original preparation. Until now, this decision was made by the treating physician. Biosimilar companies now fear that exclusive general agreements might be made for individual active substances, and that if there are numerous suppliers of a suitable biosimilar, it could lead to a destructive price-war spiral. That could result in the end in a last man left standing’ supplier for each active ingredient. But winner takes it all’ isn’t a desirable outcome.

A look at the production locations shows why the scenario would be bad for Europe. Currently, almost 60% of the biosimilar doses administered in Germany for instance are produced within Europe. If a massive discount battle were to kick off, Asian suppliers would ultimately be able to exploit cost advantages to the full, and Europe could once again grow dependent on them. Inner-European markets for biosimilars (especially in Eastern Europe) are insufficiently developed, and still offer big development potential for European pharmaceutical companies.

… follow the population

But the European biosimilar community could also try to adopt a completely different perspective for once. Instead of primarily trying to conquer the blockbuster market, it might make more sense to look to other regions in the world where the Made in Europe’ badge is still considered a seal of quality, and where large numbers of patients still don’t have access to advanced but affordable treatments. The Middle East and Africa both fit this description.

Unlike Europe, the MEA market is still considered underdeveloped when it comes to biosimilars. Biologics as a whole, however, have certainly laid the groundwork for a market there. According to a white paper from IQVIA, they made up about 15% of the roughly US$27bn overall spent on therapeutics in 2019. According to the paper’s figures, Saudi Arabia leads the pack in the use and administration of biologics by a wide margin, spending about US$2bn. Biosimilars still have a very small footprint though. They made up only around 2% of the total biologics market in Saudi Arabia, and even less in the United Arab Emirates. At a much lower level in terms of overall numbers of treatment courses, they were around 5% of all prescriptions in Lebanon and 3% in Tunisia.

Observers point out that the commercial environment in the MEA region is growing more conducive to the strong uptake of biosimilars, in light of an increased government focus on expanding patient access to medicines, budget constraints and availability of a regulatory framework. Countries there have discovered the topic of biosimilars for themselves, and usually closely follow approval rules issued by the EMA or the FDA.

The 54 African nations, on the other hand, have a patchwork of regulations and rules that can affect comparison procedures between an original biologic and any biosimilars, but also pricing. But if you can manage the diverse international European landscape, why not in Africa too? Individual European countries even offer training programmes on how countries in the MEA region, and Africa in particular, should position themselves in regulatory terms with regard to biosimilars. In 2022, for example, the German Ministry of Health’s Global Health Protection Programme (GHPP) sponsored a workshop on the Assessment of Biosimilars’. It lasted several days in the Reg-Train/Pharm-Train project, and was attended by health authority representatives from Zimbabwe, Ghana, South Africa and Tanzania. South Africa is one of the few African countries to have regulated biosimilar approval, but the first was only greenlighted in 2019.

A new area for Africa

The cost-effective drug development of biosimilars is particularly attractive for resource-constraint settings, and helps enable the availability of biologics on these markets. However, the larger molecular size and complexity of therapeutically active proteins demand specific requirements in assessing the corresponding marketing authorisation applications. Before anything can happen, assessors first have to acquire the skills needed to compare biosimilar and original biologic, as well as experience with pharmaceutical quality, efficacy and safety in the biosimilar landscape.

Some pharmaceutical companies are playing more active roles in the MEA and African regions, and investment by local and regional companies in the still largely untapped biosimilar space is flowering. Examples include Spimaco in Saudi Arabia in partnership with Roche, Julphar in the UAE in partnership with Biocad, Sedico and Pharco in Egypt, Arwan and Benta in Lebanon, El Kendi in partnership with mAbxience in Algeria, Medis in Tunisia and Sothema in Morocco in partnership with Biocad. Algerian firm Hikma, in partnership with Celltrion, launched an infliximab biosimilar in the main MEA markets, while Cipla from India has not only entered the market but also has its own production sites.

From Reykjavik to Cairo

Interestingly, Iceland-based Alvotech is one of the rare pure biosimilar players from Europe to have a business strategy in Africa. In partnership with local or other strong pharma companies, every biosimilar the firm has in development also has a specific roll-out plan for the continent. Alvotech has also signed an exclusive licensing agreement with Bioventure (Dubai), Minapharm Pharmaceuticals (Cairo) and MiGenTra GmbH (daughter company of ProBioGen AG in Berlin) for the commercialisation of multiple biosimilar candidates in Egypt and 18 additional countries in Africa and the Middle East. The partnership will now see the latter companies share the launch and marketing responsibilities of Alvotech-manufactured biosimilars in these regions. This kind of network approach might provide a template for overcoming the fragmented African health space, and pave the way for more European players with experience in both drug development and production. That will be key for African market penetration, as infrastructure for the logistics of biologics drugs and their application to patients is still often missing.

And there’s a final reason for biosimilar makers to focus on emerging markets like those in the Middle East and Africa. In places where an original biologic had little impact because it was never widely available, biosimilars don’t have to fight unfounded beliefs they’re just cheaper or bad copies’. The doors and markets are open there for European biosimilar developers and manufacturers. But the clock is ticking.

Polpharma Biologics SA

Polpharma Biologics SA Sandoz

Sandoz market.us

market.us