CARs right on track

Since reports that blood cancer response rates to T cells carrying chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) exceed 80%, investors have been laying bets on CAR-T cell approaches. In August, the first two therapies hit European markets in a head-to-head race to be the number one next-gen cancer therapy. So will CAR-T cell treatment really take pole position? Or will alternatives like TCR-based cell therapy or multivalent antibody-T cell engagers leave them in the dust?

The story of eight-year-old Kaitlyn from Dallas sounds like a Hollywood screenplay. After being diagnosed with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in 2011, she was one of the 15% of patients that relapse from chemotherapy. After two and a half years of chemo, with every recurrence bringing a worsening prognosis and drop in quality of life, she was given a one-time CAR-T cell infusion within a clinical trial. Previously, her own T cells were engineered outside her body to carry a receptor activating them to attack cancerous blasts upon binding the cell-line specific CD19 surface marker. When reinjected, they proceeded to wipe out her cancerous and healthy B cells. In September 2017, according to US broadcaster CNBC, she had been in remission for almost three years.

It’s still too early to know whether Kaitlyn is an isolated case. But clinical data from two FDA- and EU-approved CAR-T cell therapies, as well as results from late-stage clinical trials, suggest she might not be. According to Seeking Alpha analyst Bill Koski, over 80% of the 75 children with chemo-recurrent B-ALL responded to Novartis’ Kymriah (tisagenleucel) in the pivotal ELIANA trail. 60% of those exhibited a complete response (CR). The therapy was greenlighted by the FDA in August 2017, just five years after Novartis licensed it from Carl June at the University of Pennsylvania. Just a year later, the EMA followed suit.

The short time-to-market and low patient numbers (well below 100) required for accelerated market authorisation have helped trigger a wave of company foundations, multi-billion M&As, licensing deals, and a burgeoning crowd of CAR-T cell candidates. 354 are currently in pipelines, 76% of them in preclinical testing. The pricing for CAR-T cell therapies has contributed to the surge.

Kymriah, which is made individually for every patient, has an outcome-based price tag of $475,000 in the US.

If we don’t see a complete response by 30 days, they don’t pay for the therapy, explains Liz Barrett, CEO of Oncology at Novartis, adding that there haven’t been very many cases where it didn’t work. According to her, there are about 300 patients in the relapsed, refractory patient population in the US. A further 300 patients per year are in other target markets. In early September, the British National Health Service (NHS) agreed to reimburse Kymriah at well below the European list price of US$363,000 per B-ALL patient, a spokesman at the UK’s health technology assessor NICE told European Biotechnology.

A huge and hopeful market

However, Novartis and other CAR-T cell players – like Celgene, bluebird bio or Gilead – are focusing on blood cancer indications with much higher patient numbers, because they translate into better profits. It’s important to keep in mind where CAR-T is going. You start in the later lines of therapy, because that’s where the highest unmet medical need is, says Barrett. But we’re planning clinical studies in earlier lines of therapy where patient populations are much larger. Catching patients earlier will hopefully prove better for everyone, she remarks.

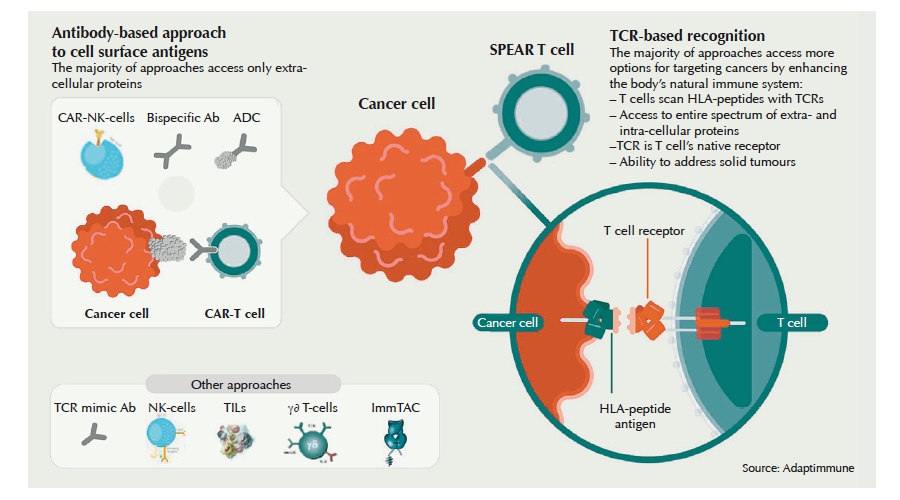

And of course the real hope is not only to treat blood cancers – which make up just 10% of all cancers – but solid cancers as well. They’re already being targeted by companies like Eureka Therapeutics, Celyad NV, Minerva Biotechnologies, Autolus Ltd and others. A range of academic groups and companies in the US and Europe have begun to seek ways for CAR-Ts to overcome the T-cell-paralysing microenvironment in solid tumours, and an array of clinical trials are underway. Even with no proof their approaches could work, companies are getting IPO valuations in the hundreds of millions, and R&D investment is skyrocketing. Everyone is trying to jump on the bandwagon, says Martin Schleef, CEO of Plasmid Factory. In the last two years, we’ve seen a huge rise in the scale of orders for high quality plasmids needed to make lentiviral and non-viral vectors used in CAR-T cell engineering. This year we had to expand our production capabilities, he says. And the cell therapy hype isn’t limited to CARs, but also includes T cell receptors (TCRs) engineered to recognise tumour targets with high affinity. Companies like MediGene, Immunocore or Adaptimmune argue that targeting solid tumours with optimised TCRs is the better strategy, because unlike CARs, TCRs can recognise intracellular cancer antigens presented by the cancer cells’ major histocompatibility complex (MHC). It’s the early laps in what promises to be an exciting race. In addition to Novartis, just one other CAR-T specialist has reached the market so far: Kite Pharma/Gilead Sciences.

Barreling down on the market in Europe

In October 2017, the Kite Pharma arm of Gilead Sciences – two months before it was acquired in a US$11.9bn deal – received FDA approval for its CD19-targeting CAR-T cell therapy YescartaTM (axicaptagene ciloleucel) in chemo-refractory adults with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). It’s a patient group of approximately 6,700 adults per year – ten times more than B-ALL – and it represents US$5bn in sales, according to Seeking Alpha analyst Koski. In May 2018, Novartis’ Kymriah received its second FDA approval in DLBCL. Koski reports that in this indication, Yescarta – priced at US$373,000 per patient – clearly outperformed Kymriah in its pivotal ZUMA-1 trial, with 82% response in 101 patients, and 58% of them CRs. Among the 81 participants in Novartis’ JULIET trial, the response rate was just 50% (32% CRs).

In Europe, however, where both therapies were granted market authorisation at the end of August, Kite/Gilead already lost a head-to-head race against Novartis in the first of its target markets, the UK. The Swiss giant has had a remarkable run of good luck. First, the EMA downgraded Gilead’s fast-track status for Yescarta’s MAA, which Kite Pharma had submitted two months earlier than Kymriah, to better understand the data. Then the UK health assessor NICE rejected reimbursement of Yescarta on the day it was approved in the EU, arguing that the drug’s incremental cost-effectiveness ratio more than doubled the threshold of £50,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) vs. standard-of-care. What’s worse for Gilead Sciences, which wanted to roll out Yescarta in Germany, Austria and France in addition to the UK, is that its CAR-T cell therapy did not meet the criteria required for coverage by the UK’s Cancer Drugs Fund, which provides patients access to cancer drugs that would not otherwise be available from the NHS.

Beyond the hype – still a long way to go

While the first two CAR-T cell therapies have been approved, a lot of questions remain to be answered. Topping the list:

- The huge prices of autologous therapies, which producers justify with the laborious CAR engineering into T cells, their expansion, and delivery back to the hospital, where the individually produced autologous CAR-T cells are reinfused into the patient.

- Safety. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) occurs often upon CAR-T reinfusion, and seems correlated with response to therapy. A second life-threatening adverse effect is neurotoxicity.

- Durability of response, as early CAR-T cell death and therapy resistance often lead to recurrence of the cancer.

Currently, T cells are isolated in certified hospitals, then shipped to approved production centres or CDMOs. There the T cells are genetically modified to carry a chimeric antibody receptor consisting of a tumour-antigen (i.e. CD19)-binding single chain antibody fused to a signalling domain, which is made up of co-stimulatory T cell receptor fragments and the CD3 protein (see figure to left). These trigger T cell activation and proliferation upon binding the tumour antigen.

While Novartis, Kite/Gilead and other relevant players claim the expensive manufacturing process is at the root of the huge therapy cost, two blood cancer patients published a different calculation this year, arguing CAR-T cell therapies were significantly overpriced (Health Affairs, doi: 10.1377/hblog20180205.292531). The authors – PR expert David Mitchell and ex-Lek Pharmaceuticals CEO Paul Kleutghen – estimate that even if Kymriah cost just US$190,000, Novartis could afford to invest 19% of its earnings in R&D and still generate a profit margin of 65% – more than twice what the company generates on its current product portfolio.

While Novartis spokesman Eric Althoff stresses the authors’ assumption of US$20,000 for cost-of-goods is false, experts in the field have told European Biotechnology that their estimate is close when it comes to pure material costs, but that costs for labour, infrastructure, logistics, etc. would lead to a total manufacturing price tag of at least US$100,000.

For payors, the current cost of cell therapies is burdensome, even in more common orphan blood cancers such as multiple myeloma, an indication with 30,000 US patients per year targeted by anti-BCMA CAR T cell therapies such as Celgene’s bb2121 or Poseida’s P-BCMA-101. Because healthcare systems find it difficult to set appropriate pricing models for such expensive one-time-treatments, players like Roche or Amgen haven’t stepped into the field. Instead they’ve stuck with antibody-based methods for activating T cell responses like bispecific T cell engagers (BITEs). These can be produced more cheaply, with up to 80% complete responses as shown by Amgen’s multiple myeloma-BITE AMG 420 in September. Still, improved antibody formats such as IgG1-like bispecifics compete with TCR- and CAR-T-based cell therapy approaches.

Off-the-peg vs. tailored

In April, a company claiming to be able to solve the price problem with autologous CAR-T cell therapy closed a US$300m Series A round. Allogene, which was founded by the managers that sold Kite to Gilead, has taken over pipeline candidates from Cellectis SA’s licensees Pfizer and Servier. They now say genome edited allogenic CAR-T cells with switchable T cell activity are the future. Cellectis CEO André Choulika believes donor T cells cleared of antigenic determinants by genome editing could be manufactured off-the-peg, driving prices for treatments down to US$10,000/patient. But skeptics predict the immune system will always recognise allogeneic CAR-T cells sooner or later, and think that even in a best-case scenario, they would only bridge the gap to stem cell transplantation – but not provide long-term solutions to hematological cancers.

Cutting down on side effects

Beyond the issues of manufacturing and delivery costs, severe side effects are still a major concern in T cell immunotherapy. Kymriah (costimulatory 4-IBB domain) triggered severe (grade 3+) cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in 46% of B-ALL children and 23% of DLBCL patients, but neurotoxicity was low (13% in B-ALL, 18% in DLBCL). Yescarta (costimulatory (CD28) domain) triggered cytokine storms in just 13% of subjects enrolled in ZUMA-1, but led to neurotoxicity in 31% of them.

While clinicians can manage CRS with Roche’s IL-6 receptor blocker tocolizumab, research into blockers of CAR-T-triggered seizures and encephalopathies like brain edemas is still in its infancy. In August, Attilio Bondanza from San Raffaele Hospital (Milan) and Michel Sadelain from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York) showed in mice that genetic or pharmacologic (with Anakinra from SOBI AB) depletion of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 helped prevent both neurotoxicity and CRS. Side effects may also drop with more defined cell therapy products. Researchers at the Fraunhofer IZI, a European manufacturing site for Kymriah, told European Biotechnology that only 20% of viable cells carry a CAR construct. Higher proportions of CAR-T cells in the end product might reduce cytokine release by non-CAR-T cells, thus possibly reducing IL-6- and IL-1-triggered adverse effects.

Making cures permanent

Given their high price, developers are working on ways to assure long-term efficacy in CAR-T cell therapies. Increasingly, a high relapse rate after CD19-targeting CAR-T cell therapy has emerged as a major problem. Less than half of patients with DLBCL who receive CAR-T cell therapy are still in remission a year later, says Jeremy Abramson from Massachusetts General Hospital, adding that single-target therapy may select for and lead to escape variants. One possible workaround is targeting additional B cell antigens CD22/40/75/76 or combining CAR-Ts with other immunomodulators. This might prevent resistance when the tumour no longer exhibits CD19 antigens on its surface. Solid tumours are even more problematic. They can go into stealth mode by erasing all antigen-presenting proteins from their surfaces, a process called antigen-shedding.

Many avenues to progress

CNBC didn’t respond to our enquiries about the current state of Kaitlyn’s health. Three years of survival is a great start, but currently no one knows whether other subjects will show similar long-term remission. Or whether in the end, CAR-Ts, TCR-based approaches or follow-up drugs to Amgen’s fully approved bispecific T-cell engager (BITE)-based ALL therapy blinatumomab, will provide the best solution for cancer patients.